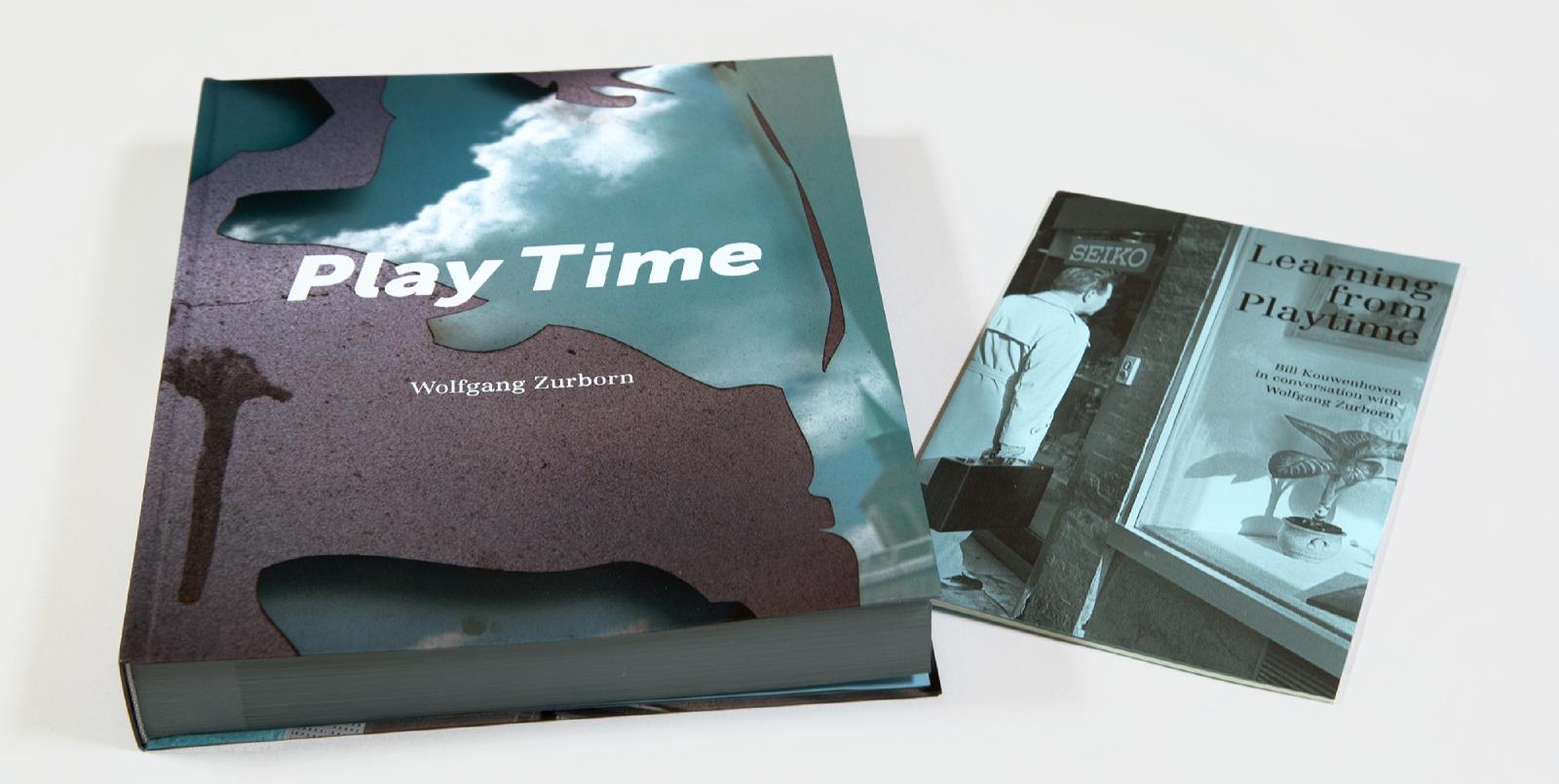

Play Time

Play Time

Fotohof edition 2021

Band 332

ISBN 978-3-903334-32-8

272 pages with 220 colour images

Size: 21x27,6 cm

Flexocover

39,00 €

Accompanying Booklet

Interview by Bill Kouwenhoven

with Wolfgang Zurborn

24 pages with 10 black and white images

size: 13,5x21 cm

Design: Frederic Lezmi

Production: Druckhaus Kettler

Texts: Quotes by and about Jacques Tati

12 Motifs

Edition 20

FineArt Inkjet Prints

on Hahnemühle paper “PhotoRag 308”

20x30 cm

Photographs

| Solo exhibitions | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2022 |

Play Time Museum Tempelhof, Berlin, Germany |

|

| 2021 |

International Meetings of Photography 2021 Certificate of Presence Balabanova House, Plovdiv, Bulgaria |

|

| 2020 |

Sights Sights Iris BookCafè & Gallery, Cincinatti, United States |

|

| Group exhibitions | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2022 |

Schichtungen des Realen Kunsthaus sans titre, Potsdam, Germany

25 Sep 2022

-

30 Oct 2022

|

|

| 2021 |

Listen to the Photographs Pop-Up-Raum, Hamburg, Germany |

|

| 2021 |

one artist - one minute Künstler:innen aus 40 Jahren FOTOHOF Stadtgalerie Lehen, Salzburg, Austria |

|

| 2020 |

Floating Identities Kunsthaus sans titre, Potsdam, Germany |

|

| 2019 |

Vonovia Award für Fotografie 2018 zum Thema “Zuhause” Kommunale Galerie, Berlin, Germany |

|

| 2019 |

German Street Photography Festival Hamburg, Germany |

|

„Seeing instead of wanting to mean“

Interview by Bill Kouwenhoven with Wolfgang Zurborn in accompanying Booklet

with photographs from the series Frontgarden of Illusions

BILL: Some twenty years ago, when your book dressur real was published, I described you as the least “German” German photographer. That was, of course, in relation to the Struffskys (Struth, Ruff, Gursky), the Becher School, and the Tillmanns and Tellers of the following generation. Do you still think that you are the least “German” German photographer out there now? Obviously, I don’t mean this in any sort of “nationalistic” sort of way but rather in a stylistic one.

WOLFGANG: Yes, I do still think this is true. In the meantime, of course, there are many more different stylistic currents in German photography other than just the Becher School. There is a far wider spectrum of artistic positions created here in Germany than is generally known internationally. You are right to say that my artistic roots definitely don’t lie in the classic German style of documentary photography. When I was studying photography in Dortmund back in the 1980s, I was confronted with the demand to produce the most neutral representation of living spaces and the urban environment. “Reality” was to be represented almost exclusively by scenes of streets devoid of people and the desolate façades of houses. I have to say that during my time at school it was the films of Jacques Tati that inspired me, with their social realities and the grotesque contradictions rather than any sort of single “objective” reality.

BILL: Tati had much of a live and let live aesthetic. Life also has its problematic sides, such as now when we are confronted with Covid-19 and all its ramifications, but we still have to find a way to live and to maintain a sense of humor through it all.

WOLFGANG: Absolutely! Humor is one of the most important parts of my work, and it is what I find lacking in most of the current influential positions of German photography. There is scarcely any trace of self-irony. The dominant belief is that it is possible to create a scientifically rational cataloging of the world and I have always found this kind of thought to be deeply suspicious. That doesn’t however mean that I disrespect those other positions and their achievements in the history of photography.

BILL: You stand completely opposite the traditions of Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity. For a long time, these movements so dominated art and photography that they produced a kind of single-minded tunnel vision and that deeply informed teaching at some of the leading photography departments such as in Düsseldorf and at Yale. I am curious to know, how important is it that you live in Cologne rather than, say Düsseldorf?

WOLFGANG: That’s a surprising question. There is of course the perpetual conflict between Cologne and Düsseldorf, which has deep historical roots and is carried out in a fun and in a serious way at the same time. It’s a kind of love-hate relationship. Although these two cities are practically neighbors, they represent completely different attitudes towards living. I was always drawn to Cologne. For the past thirty-four years Tina Schelhorn and I have directed Galerie Lichtblick there together in order to create a vital space for the presentation of the most diverse positions of artistic photography. Another completely different experience for me was seeing the Cologne Carnival. Although I was previously rather skeptical about engaging with masses of people, I have totally embraced it as a theatre of real life played out in the city’s streets since. Theatricality and truthfulness are no longer opposites as far as I am concerned. This openness to the world is something that I deeply associate with Cologne.

BILL: Yet Carnival is celebrated up and down the Rhineland. Are there any specific differences between Düsseldorf and Cologne? Is there a different sort of lifestyle or sense for a quality of life between the two cities?

WOLFGANG: A quote comes to mind: “Düsseldorf looks the way it does because it is as though the advertising photographers believe the myths they produce.” Düsseldorf is a city that is strongly influenced by the fashion and advertising industries. I find it smoother than Cologne which seems to have a more heterogenuous structure of diverse social classes it is a working class as well as a media and art city. The motto of Cologne is “Let everyone do as they please,” and this liberal attitude toward those who think differently is not merely a myth. In reality unconventional approaches can find a home here in Cologne. One finds a lot of Cologne’s attitudes towards life in general represented in Chargesheimer’s photography from the 1950s. He was really one of the very first street photographers in Germany and one of the few who really captured the feeling of life in the streets in an unpretentious way.

BILL: Heinrich Zille also brought the street life of Berlin into his sketches and photographs. His work has a sweet, yet absurd quality. His version of the everyday reminds me of something out of a Fellini film.

WOLFGANG: Yes, you are right about that. He was another very early representative of what we now call street photography in Germany. Other than Zille, there is very little street photography in Germany because chance and momentary photography, that is to say, snapshots, are often excluded and regarded as something arbitrary, as something “non-conceptual”. That is something I find completely incomprehensible because the aspect of the artistic medium of photography that I find most special is its ability to capture the unscripted moments of everyday life. You can see that with my own photography, I have been influenced far more by American photography and photographers such as Lee Friedlander whose work I adore.

BILL: What about Garry Winogrand?

WOLFGANG: Of course! Obviously. Garry Winogrand and William Eggleston, too, naturally. The American style of street photography and documentary photography has always influenced me the most. When I was a student, I did a presentation on Walker Evans who also influenced me a lot. He never says that he wants to depict reality objectively in his photographs but rather that he understands photography as the most subjective form of expression. Thus he spoke of a documentary style where he engages in a dialog with reality and finds images that also correspond to “inner” images. The aim was not to suppress subjectivity in order to produce an objective, “real” image of the world. The conceptual restrictions of German documentary photography don’t exist in American documentary photography.

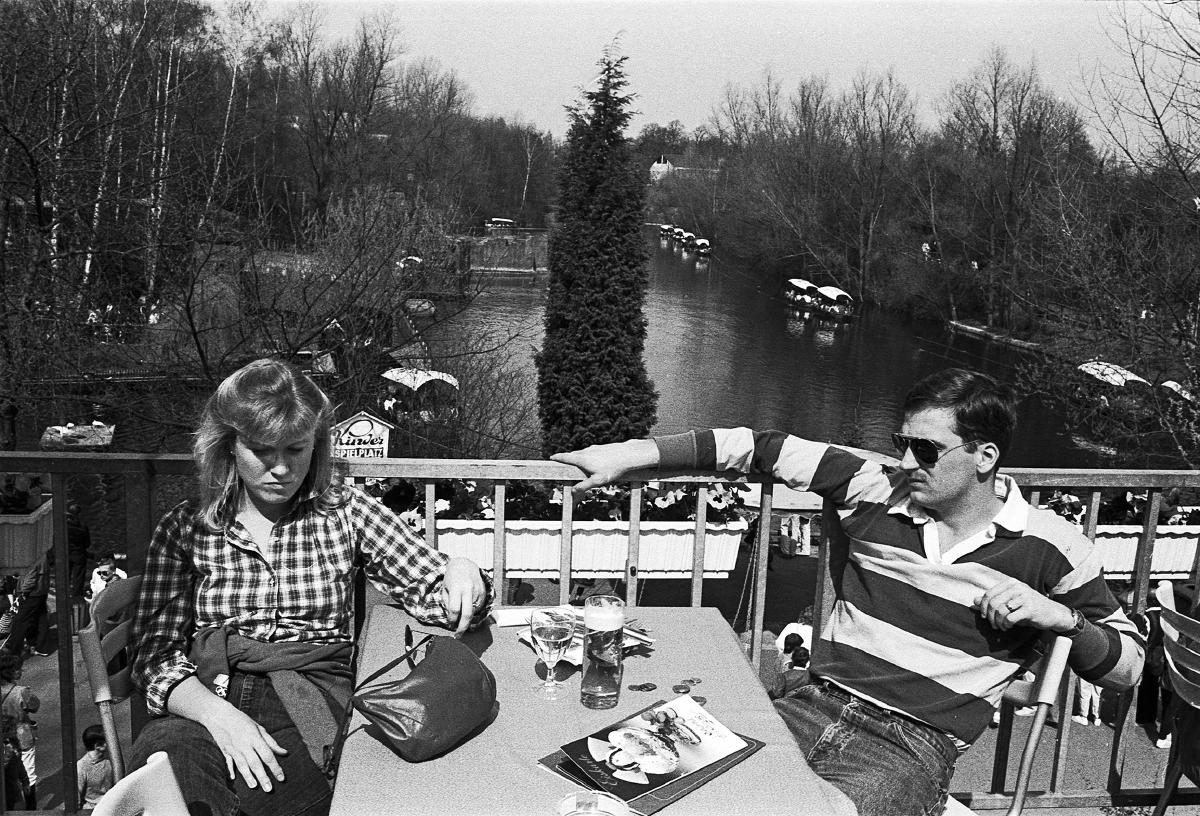

BILL: Two questions: How do you think your work has evolved in the twenty years or so that we have known each other, and second, and — this is something that is very interesting to me — as I was going through the images in Play Time a question arose. Let me phrase it this way: normally color photographs, and especially color street photographs of social situations capture specific moments of fashion, of haircuts, of cars and advertising, say, that are easily dated. Yet your photos from Play Time seem relatively timeless. They could have been photographed almost at any time during the last thirty years except where specific film posters or cartoon figures, for example, appear. There are relatively few people in the images and the situations you photograph could be more or less anywhere in any industrial or post-industrial city. This mélange of images from three continents across five years is, in effect, timeless. One seldom sees this in color photography, and this is something rather unusual, special even. How is this?

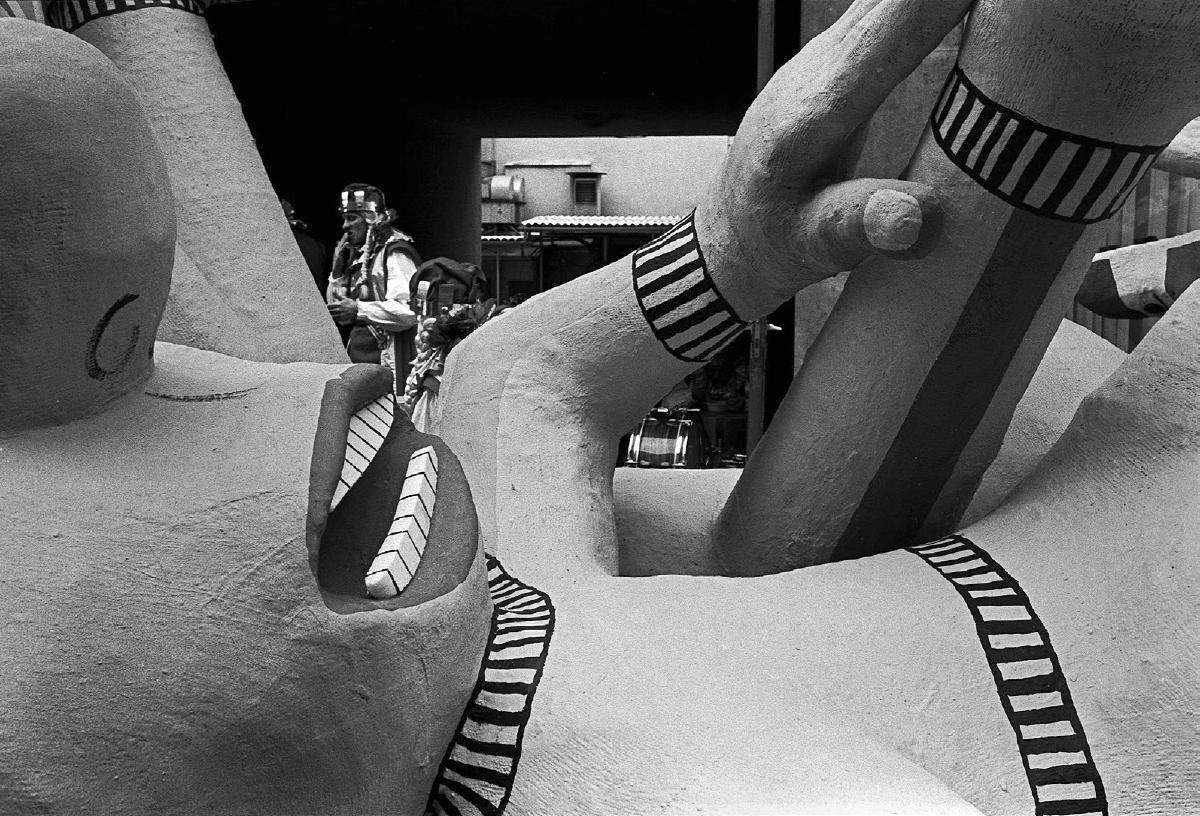

WOLFGANG: In my series, Menschenbilder – Bildermenschen, from the 1980s, I photographed people at mass events. It was still very important for me to show people in their environments and to capture complex moments with situational photography. When I finished this series, I started to wonder about how I could develop my photography further. I was aware of the fact that the heart of my photographic intent was not to create ironically witty or, as Martin Parr has often done, sarcastic images from moments of everyday life. It was more important to me to produce images that were more ambiguous. Back in the early 1990s I put together my series Im Labyrinth der Zeichen by assembling fragmentary details and unusual perspectives, building montages that presented a sort of visual puzzle. The viewer was thereby forced to look at the images closely and to unravel the associative networks that link the individual multifaceted elements contained within the images. This montage technique was carried over into my following project, dressur real through an unconventional form of editing individual images together. I combined situational shots of street scenes with abstract images from the requisites of everyday life in such a way that I was able to create works that alternated between a long shot and a detailed close-up that functioned like a zoom cut in a movie. With my next book, Drift from 2001 I deliberately selected a vertical or “portrait” perspective through which I developed a different style that allowed my images to move on the interface between representation and imagination, and between document and enigma. All of these images offer an ambiguity and often detach themselves from their actual, real-time associations and contexts in a way, that as you suggest, makes them seem timeless. What is important to me is that these images act as a catalyst for the imagination of the viewers.

BILL: When you take away the contexts, a sort of “everyday Surrealism” is formed. Many of these images make use of reflections or distortions of perspective through mirrors and shop windows and the occasional plexiglass of bus stops and the like. One sees half of something and the partial reflection of something completely different—or the juxtaposition of things that are everywhere but that most of us completely overlook. Over the years how do you think you have developed your eye for finding these motifs?

BILL: In the last 15 years you have led countless workshops all over the world. Have the workshops had a side effect or any sort of direct impact on you so that you see differently or have you yourself learned from working with students? How has this worked out for you?

WOLFGANG: I must admit that I have learned a great deal from some of the workshops. And I have never felt that the workshops have taken any energy away from my own projects. When students present work before you and you have to analyze the work in a short amount of time without losing sight of the very real personality of the photographer, then you are responsible for whether the person to whom you are providing the critique is getting a perspective that will help them further with the project. Thus, you have to be open to all sorts of different strategies. If you are too dominant and present your own perspective as the measure of all things, that will never work. To be open to ideas without losing oneself is the most important thing that can result from these workshops for me and it can have a great impact on one’s own work. This openness is also carried through in the spirit of Play Time. It is not about trying to present one photographic vision as the right way of seeing things or to visually substantiate ideological claims. Photography is something I understand as a wonderful medium of dialog with the world that facilitates a kind of cross examination of the myriad forms of contemporary life. “Listen to the photographs” is a really important motto of my workshops. I think the strongest works emerge through the interplay of an intuitive process of photography combined with the conceptual development of editing. The imposition of rigid concepts or clearly defined themes degrades photographic images to the mere illustration of texts. Images have their own personal language, and all of my workshops aim to help each individual student to develop their own visual language.

BILL: Do you photograph differently in Shanghai, New Delhi, or for that matter, in Cologne? Of course, you let yourself be guided by your various surroundings, but there are times when I can seldom see particular differences in the pictures from one country to another. It seems to me that you photograph everything similarly and are creating your own visual world.

WOLFGANG: Yes, I think that each photographer carries their inner images around with them, but it is important that they also react differently to different environments so that one’s vision does not get too habitual. When you look at my book from 2018, Karma Driver, you can see a great difference as opposed to Play Time. In India it was very important to me that I combine the classic landscape format of traditional street photography with scenes from Indian megacities to bring out the quality of life and the chaos in public spaces as strongly as possible. Together with the more abstract “portrait” format, images of symbols of contemporary Western and Eastern culture, these photographs form a sort of inexorable Bilderstrom or flood of images from which there is no escape. The method used to assemble the two-page spreads varies very strongly across all of my previous books and invokes different ways of interpreting the images in the reader. One can say fundamentally that my images from Germany are often more enigmatic and even abstract compared to the others because this world is more familiar to me. I can only produce images when something new is happening on the picture plane itself. A mere image could never satisfy me. When I am in other countries the situation is often different because the surroundings are unfamiliar to me which allows me to give in to my curiosity and to explore my new surroundings. That really comes out in the series China! Which China? that I published in 2008 as a large format Leporello.

BILL: I find that your pictures also remind me of the torn posters by Robert Rauschenberg which Andy Warhol made famous to a certain extent. There are the various levels, layers, the overlayering of other visual languages and genres, that all exist at the same time in the same visual image, even if pasted over by newer posters. They are not conceived as with a collage by a single artist but rather they are like the random sculptures and found images we find every day in the world around us. This fascinates me, and I find many of these in your collection of images.

WOLFGANG: Yes, this is definitively an important influence. Rauschenberg definitively had more influence on my photography than the Becher School. I love Rauschenberg’s work and was very happy to meet him personally and to experience that he could look at my own photography and understand what I was doing with it. Painters often react more strongly to my images than pure photographers. In the American press there were direct references to American Pop Art painters especially to James Rosenquist. The Dallas News wrote about my exhibition at the Photographs Do Not Bend Gallery that what was unusual about the images was that on the one hand they showed the most banal aspects of everyday life but on the other hand they were dramatically exaggerated because they were like paintings in that they were meticulously composed down to the last detail. That’s where the joke lies which has rarely been understood in Germany. The charm, if you will, has less to do with an obvious punchline but rather lies in the more “grotesque”, even silly combinations of various picture planes. That is where there are actual parallels to Jacques Tati’s legendary 1967 film Playtime for me. If one looks at the very first scene at the airport, nothing particularly special occurs. It is only a series of very long takes, but this in itself is so funny that the first time I saw it, I dropped to the floor laughing. It is wonderful that the humor does not revolve around ridiculing people. That would totally put me off. This is where I find a spiritual kinship with Jacques Tati, and yet it is totally clear to me that the photographs in my book Play Time are, of course, stylistically completely different from Tati’s filmic images. This is also extremely important because I do not wish to copy his images. What is important is that we share a humorously critical look at modern times.

BILL: What you see and what you find is in front of your eyes and, therefore, your camera. Those things are, of course, in front of everyone else and their cameras too, but either they ignore these things because they are busy working or otherwise lost in their own thoughts. These things, these images, are to be found if you only have eyes to see them.

WOLFGANG: That is exactly what I found in the citations from Jacques Tati. He said that the most important thing that someone could later say about him is that he had learned to see. This is important in our modern society too, in which human beings are conditioned to only see what conforms to our society and how it functions. Another motto of my workshops is “to see something is more important than to mean something”. It is not about trying to make some sort of definitive statement about this or that, but it is rather about being able to see anything that will give rise to subjective feelings. Anyone can find such pictures anywhere or nowhere at all. This is something that cannot be planned, and this idea is something that was intrinsic to my book Play Time where, as I was going out to different places to find images, I was not following any sort of specific plan. I would ask myself every morning, “what am I going to do today?” I never knew what to expect, whichever new city I found myself in. So I’d land, say in Mönchengladbach or in Neuss, really unspectacular places, unremarkable actually, without any intention of visiting this or that particular event. This also represents a major change to my work in Menschenbilder – Bildermenschen where I deliberately attended political, sporting and cultural events and manifestations in order to make statements about this kind of event culture. An attitude that runs through all of my photographic work is that I want to present structures that do not reveal the actual chaos that is occurring. For me, it is not about tidying up the world but rather about giving structure to the everyday chaos of the world so that one can experience it. In my scenes of the mass events back in the 1980s, more than twenty people were often visible at once on different image planes,which probably makes these photographs the most similar to the cinematography of Playtime. The various narratives, the snapshot aesthetic, the collage-like, enigmatic and abstract modes I used as different levels within the grammar of my photographic language flowed playfully together into what became my own book, Play Time.

BILL: It is really wonderful when the world collaborates harmoniously with one’s images and vice versa, and it makes for a beautiful melding of perspectives.

WOLFGANG: As I’ve been going through my archive of earlier images from the 1980s during this period of being locked down due to Corona and scanning hundreds of pictures from those public events, it has become clear to me that the way I was photographing people then — using medium format with flash, standing about a meter away from the people I was photographing—I could never work that way any more. I would be hauled off by the police immediately nowadays. The situation has changed dramatically and as a photographer you naturally have to react to that. That does not mean that because of this I cannot take pictures of people in public spaces anymore. The stylistic changes to my pictures in Play Time had other reasons. The ambiguity and the pleasure of seeing comes first now—even if this entire series is ultimately a critique of modern society and its values. Even in his own film Jacques Tati is an acute critic of modernity without being a traditionalist or a Romantic who views every development of our contemporary society as a disaster. He also has such a love-hate relationship with society, otherwise he would never have made the immense effort of building Tativille, his own “city” as a set and stage for the film. In his attitude toward modernity there is no simple good or evil. There is a further point to Tati’s world, and that is his love of dance. Tati came from the world of performance and so movement and dance played a very important role for him. There is the famous dance scene at the end of Playtime where the decorations and the actual architecture of a night club falls apart as a wild party erupts and everything ends in the mayhem of joyful chaos. This scene was a kind of trigger for me that has always encouraged me to break out and dance at countless conventional events. I only realized this later and yet it still plays a very important role for me. It is about the physical experience of the world and not about any sort of imaginary world.

BILL: I was always a Fellini freak and came to Tati much later. It must have been the other way around for you. Fellini came out of the Neorealism of postwar Italy with his very realistic take on society, yet he also let his sense of phantasy take over that enabled him to film the absurdities he found there in his own world. Tati, especially with Playtime took his scenes more or less from what passes as reality. His world, compared to Fellini’s, seems more plausible. The famous traffic circle scene with its resemblance to a carrousel is perhaps a counterpart to the equally famous traffic jam in Godard’s Weekend. In any case it is somehow much more amusing than Godard’s games of automotive chaos.

WOLFGANG: Exactly, all the filmmakers you have named have been major influences on my own way of thinking about imagery. I have to say that the movies in general have inspired me far more than still photography. The Autorenfilmer, the more independent directors, were especially interesting to me and of course they were equally as inspirational to the more independently minded photographers or Autorenfotografen.

BILL: Fellini’s world is an artificial construct, but with Tati, Tati’s world mirrors the absurd realities of the then contemporary Paris and France. That is an exciting contrast: Fellini constructs his world but Tati finds his own world.

WOLFGANG: This reminds me of a quote from Tati. “The best critique I ever received came from the letter of a 14 year-old kid who said that the best thing about the film was that after leaving the cinema, the film continued in the streets”. And that is exactly what you described. This film sensitizes the viewer to the absurdities of everyday life. Thus when I was a photography student back in the 1980s in Dortmund I felt exactly like a 14 year-old boy who had just seen Tati’s movies and then went out into the world, into Westfalenpark, to find images that were like a journey through time for me, into my childhood where I could see through the eyes of a child again.

BILL: I think it is always very, very wonderful to see different places and different people with fresh eyes. That is a gift that you have given us with your images over the years and now especially with those in Play Time.

Bill Kouwenhoven (Baltimore, USA, 1961)

is an independent curator and freelance critic who lives and works between Berlin and New York. With more than

twenty-five years of experience, he is the author of more than sixty artists’ monographs and has been on numerous

international juries and reviews from the Houston Fotofest, to the Rencontres de la Photpgraphie a Arles, to Kolga

Tbilisi, Photo Georgia, and Daegu International Photography Festival in South Korea. He has been editor of Photo Metro

from San Francisco, international editor of Hot Shoe, London, and has contributed to numerous European publications

including the British Journal of Photography, PHOTONEWS, European Photography and photographie.com.